Their reasons were different—nostalgia for some, the desire for a certain kind of freedom for others—but the result was the same. In 2012, two generations of electronic music fans ventured across the city’s ring road to rediscover the charms of Paris’s suburbs and industrial warehouses. On March 17, the spirit of the very first raves was resurrected in Aubervilliers with the Mozinor My Amor party. A popular Facebook group for fans of the old Mozinor, a warehouse in Montreuil where a series of legendary parties was held in the early 90s, was behind the event. This “old-fashioned” rave—the site of party was revealed at the last minute and featured retro decor—was attended by a

few thousand people, most of whom had taken part in French techno’s heyday and were happy to trot out their T-shirts from back in the day. The twenty-somethings generation also wanted to escape the Paris night scene and its expensive, snobby, and depressing clubs so they could party freely in the nearby suburbs. Throughout 2012, numerous parties, some more legal and well organized than others, popped up (and disappeared) thanks to the magic of social networks and young collectives like Die Nacht, Play, and Cracki. These groups organized everything, from the party’s sound to its decor, bar, and DJs. Raves had made a comeback in 2012.

A musician himself (under various pseudonyms such as M&Ms and Flash and Gordon) as well as a plastic artist, Olivier Degorce was also one of the first French photographers (along with his colleague at the magazine Coda, Pierre-Emmanuel Rastoin) to take interest in the French and international electronic scene and document its rise throughout the 1990s. After an initial book in 1998, Normal People, which has long been out of print, Degorce came out with a retrospective of his work, Photographies et catalogue sonore, with the publisher Dimensions Variables in 2012.

Although he was one of the French electronic scene’s pioneers and was a runaway success as part of Motorbass (along with Philippe Zdar) and Super Discount, Etienne de Crécy was nevertheless a discreet figure in the French Touch movement. My Contribution To The Global Warming, an anthology of his songs from 1992 to 2012 (available on five CDs or six vinyl records), gave a clearer idea of the significant addition this important musician made to the French electronic scene.

In 1996, the Parisian musician I:Cube, also known as Nicholas Chaix, helped define the sound of French Touch with his track “Disco Cubizm,” which was later remixed by Daft Punk. I:Cube subsequently released four albums, all under Versatile, the label owned by his friend, DJ Gilb’r. Unanimously praised by the music press as one of his best, the dancefloor-heavy album “M” Megamix confirmed in May 2012 the importance of I:Cube and his ability to explore genres as varied as house and ambient music as well as more downtempo and experimental styles. After the release, I:Cube unfortunately decided to no longer perform on stage, making him one of French Touch’s best-kept secrets.

Kitsuné, the label founded by Gildas Loaëc, who managed Thomas Bangalter’s label Roulé in the 1990s, and Masaya Kuroki, celebrated its ten-year anniversary. Since day one, it had successfully stayed true to its one-of-a-kind dual identity. Kitsuné was both a ready-to-wear clothing brand with stores in Tokyo, New York, and Paris, and a record company whose mission was to present emerging talent from the international electro-pop scene on regularly released compilations. Even though Kitsuné helped discover multiple French groups like the duo Housse de Racket, the label’s image, which was based on artists such as Two Door Cinema Club, Metronomy, and Is Tropical, was nevertheless more Anglo-Saxon than French.

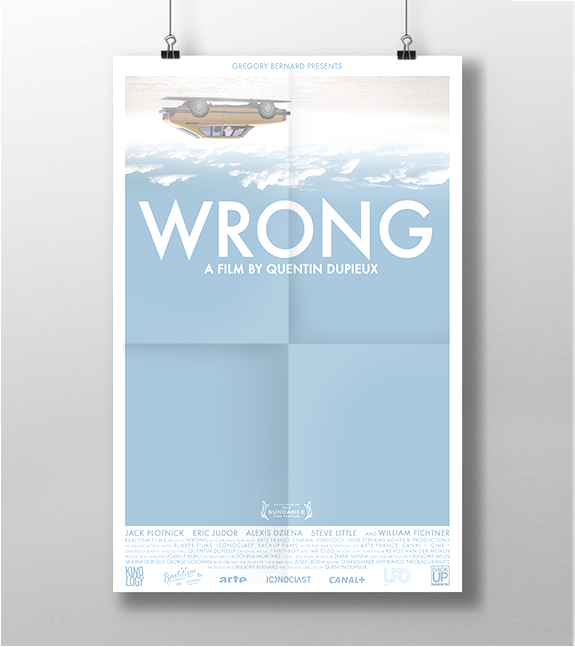

Quentin Dupieux, also known as Mr Oizo, was an unusual musician and the author of “Flat Beat” in 1999, the most abrasive hit to ever come out of French Touch. Dupieux was also a surrealist film director. After Steak, a very strange comedy with Eric and Ramzy in which numerous French electro musicians briefly appeared, and Rubber, the story of a tire that suddenly comes to life, featuring Pedro Winter and Justice in minor roles, he released Wrong, the story of a man who lost his dog. Filmed in the United States, where Quentin Dupieux mainly lived, using the video function on a Canon camera, this fourth feature-length movie was commonly considered the director’s most successful work.

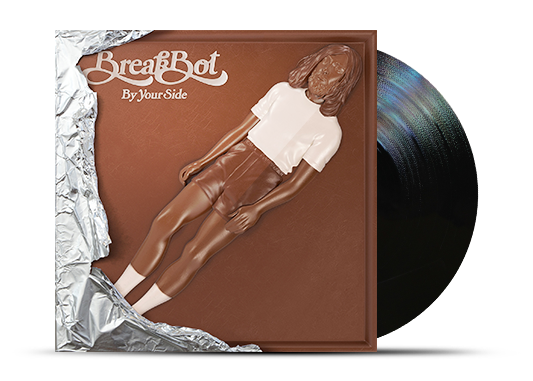

Following his funk 2010 hit, “Baby I’m Yours,” Breakbot (Thibaut Berland) released Baby I’m Yours under the Ed Banger label. This first album was just as warm as the single. Out of all the artists in Pedro Winter’s stable, Breakbot was the most passionate about African-American music and the combination of pop, disco, and funk influences. The album contained full-on summer music, and despite its odd release date in September, found its audience. Irfane, the singer from the hit song “Baby I’m Yours,” joined Thibaut Berland in 2015 to transform Breakbot into a duo for its second (and just as funky) album, Still Waters.

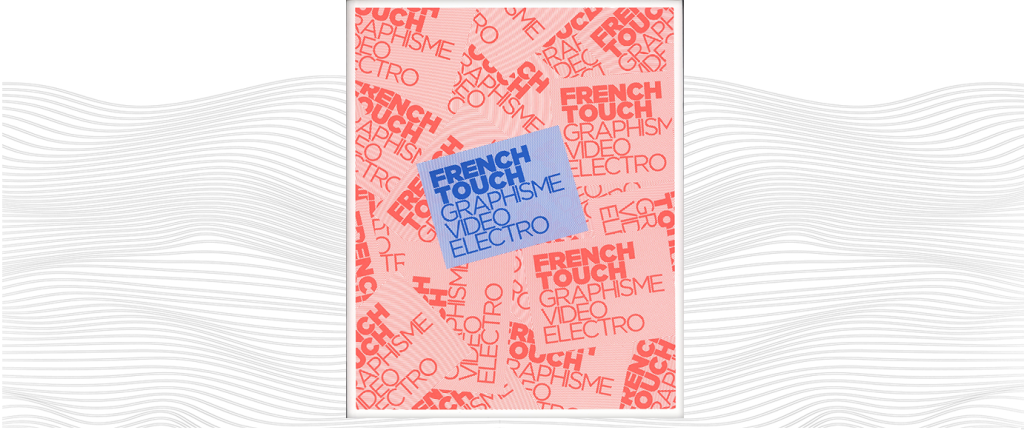

Following years of demonization, techno started to be institutionalized. In fact, it was constantly being featured in museums. In October, the Decorative Arts Museum’s new exhibition in Paris showcased the artistic works created by the French Touch movement and the close-knit ties between musicians, labels, and artistic directors in the 1990s. By presenting album covers, flyers, posters, artists’ logos, and music videos, the exhibition revealed the incredible creativity at work during a time when both graphic tools and marketing practices were undergoing dramatic change. The exhibition was designed by the team from H5, the studio behind a significant number of album covers at the time.