While England was in the midst of its Second Summer of Love and the country’s young people were blaring acid house at raves, this new way of life spread to France via a much more circuitous route. House music was only played in a few scattered Parisian clubs at the occasional one-off event. On the urging of a group of Londoners from Pure Organisation, Jungle, one of the genre’s very first parties, had been going on at the Rex Club for the past year. This group of enthusiastic Englishmen convinced the venue’s director, Christian Paulet, to preach the good news about house music during the once-a-month event. It was a success, and those same organizers moved to Le Palace shortly after for its Pyramid parties. It’s there that a young French DJ, Laurent Garnier, who had first earned his stripes at Hacienda in Manchester, put on his first few shows in France. Garnier was also active at La Locomotive, where he worked with resident DJ Erik Rug to put on H30 parties. It wasn’t the most obvious choice for a club known for its rock, punk, and even skinhead scene, as the majority of house devotees were gay and trendy.

A gay club located next to the concert hall L’Olympia, called Le Boy, quickly adopted a line-up entirely dedicated to house, techno, and new beat. After it closed in 1991, some members of the club worked together again to create Queen. Other gay clubs welcomed house music, including Broad, Power Station, and Luna.

Flyer for Sunday afternoon events at Le Boy

Guillaume la Tortue, Olivier le Castor, and Cyril Gordigiani were some of the pioneering DJs in the movement’s early years. David Guetta was also working during these pivotal years, but was mainly known as a hip-hop DJ at the time. These developments did not go unnoticed in the press; Didier Lestrade, working for Libération, was the first journalist to become interested in the phenomenon. These new forms of music were also popular in northern France due to its proximity with Belgium, where new beat had become a sensation. Hundreds of young French people crossed the border each weekend to party in clubs like Skyline and Boccacio Life.

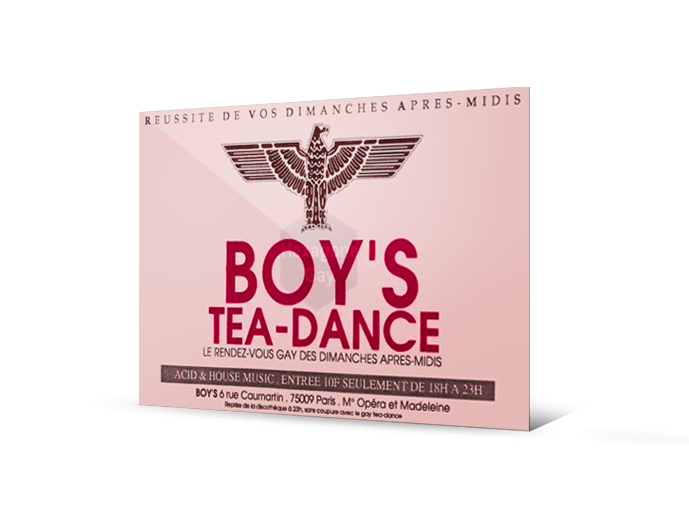

Sal Russo in front of his record store

French DJs had just a few record stores to choose from when finding raw material. Bonus Beat, opened by Sal Russo, was the first such store to only carry techno and house music. It opened in Paris near Bastille Square, which quickly became the epicenter of this emerging style. Due to a lack of customers, Bonus Beat closed for a few months before reopening as BPM.

As was the case in England, the scene developed outside of the club as well. The B.A.M collective blazed the trail as early as 1989 with the parties it organized on the Marcounet barge near Pont des Puteaux bridge. Three friends including Manu Casana, a singer in the punk group Sherwood Pogo and a diehard fan of the Paris Saint-Germain Football Club, spearheaded the effort. It was during a visit to London in 1987 that he participated, somewhat reluctantly, in his first rave. However, the combined effect of a new type of music, acid house; a new drug, ecstasy; and the concept of hosting parties in unexpected places was a revelation for him. He then sought to reproduce the same kind of experience in France, where he wanted to organize events based on pacifistic and utopian ideals. After his first under-the- radar parties at Puteaux, he joined forces with a music journalist for the French magazine L’Express, Luc Bertagnol, to put on more ambitious events under the name of Rave Age. These two former friends are now in an ongoing feud, each one claiming they have originated the name. What followed was a series of raves that remains legendary to this day, including parties at the Collège Arménien and the Fort de Champigny military base. At the same time, Manu Casana, who was also involved in the record industry through his job with a distributor, started the very first electronic music label. In a nod to his punk roots, he borrowed from Fraction Armée Rouge’s logo when designing one for Rave Age Records. The label featured international artists with whom Casana had developed a relationship, including Frankie Bones and his brother, Adam X. Importantly, the label also worked with French artists like Patrick Vidal, Christophe Monier, Electrotête, Juantrip, and the Pills duo. Though the label continued to operate until 1993 without ever truly making it big, the stage had officially been set for the electronic music scene in France.

Logo and flyer of the label Rave Age

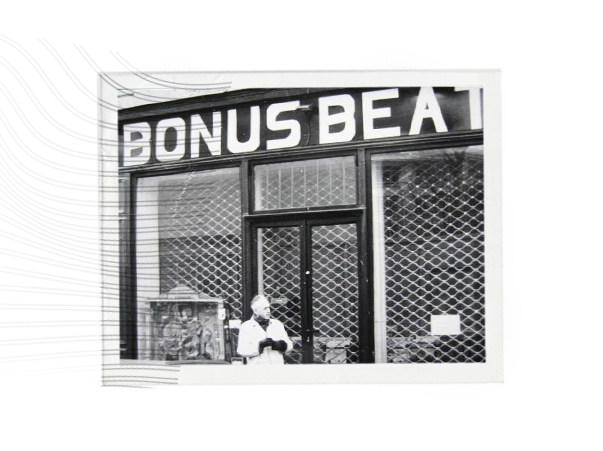

Maxi-single cover art from the Bassline Boys

Although electronic music was just taking off, it quickly garnered its fair share of criticism. That spring, “Ciel Mon Mardi,” a show hosted by Christophe Dechavanne on French TV channel TF1, aired a feature on acid house and new beat. The speakers dismissed the music as a passing fad and labeled its listeners asocial drug addicts. An even more damning report broadcast from Belgium presented clubbers as Nazis in waiting, sparking fear among the general public. In an ironic response, highlights from the program were sampled and used as the basis for one of the biggest hits in new beat, “On Se Calme” by the Bassline Boys.

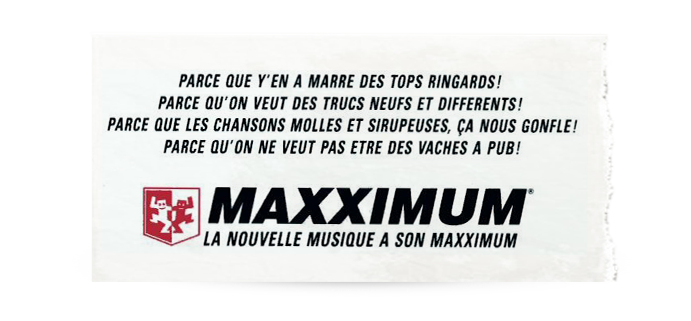

Despite the music’s unsavory reputation, radio group RTL launched a national network called Maxximum in November dedicated to house and techno. Taking note of the music’s wild popularity among the younger generations in neighboring countries, especially England and Benelux, the company tried to bring it to France. Their efforts failed, however; Maxximum went off the air two years later.

Ad for the radio station Maxximum