One of France’s first major “official” raves occurred at the beginning of the year. It took place in a room beneath the Grande Arche monument in the La Défense business district and introduced Parisian audiences to the Sheffield duo LFO. A few months before, Eric Morand from the Fnac Music label had listened to their album, Frequencies, and decided to distribute the Warp label in France. He wanted to organize a “concert” featuring the artists, whom he thought were likely to convert even the most reluctant fans to techno. Warp and LFO’s music, which was not just made for dancing, did indeed win over the open-minded fringes of the indie rock scene. To put on the event, Morand enlisted help from the young organizers behind the Happy Land raves as well as the newspaper Libération. Since the end of the 1980s, the paper had featured the column of journalist Didier Lestrade, who chronicled the early history of raves and house productions. The newspaper’s top story the day of the event was about the La Défense rave, and it released a CD recording of the live show a few weeks later.

Album cover for the live performance recorded on 1/18/92

With 4,000 people in attendance, the party was by all accounts a success. Because the event was professionally organized and held in an officially sanctioned venue with easy subway access, it attracted people who otherwise wouldn’t have ventured out to a more loosely structured party. In addition to a live performance by LFO, the rave also featured Parisian DJs Laurent Garnier, Eric Rug, and Jérôme Pacman. Libération continued to support the techno scene, launching for example the information service 3615 RAVE.

The Rex Club continued to be a focal point in the techno scene. Following the historic Jungle parties and the equally famous Space events, Eric Morand and Laurent Garnier started hosting Wake Up. Every Thursday, prestigious international DJs, especially artists from the Detroit and Chicago areas, were invited to perform. The events were also a testing ground for local productions out of the Fnac Music Dance Division label.

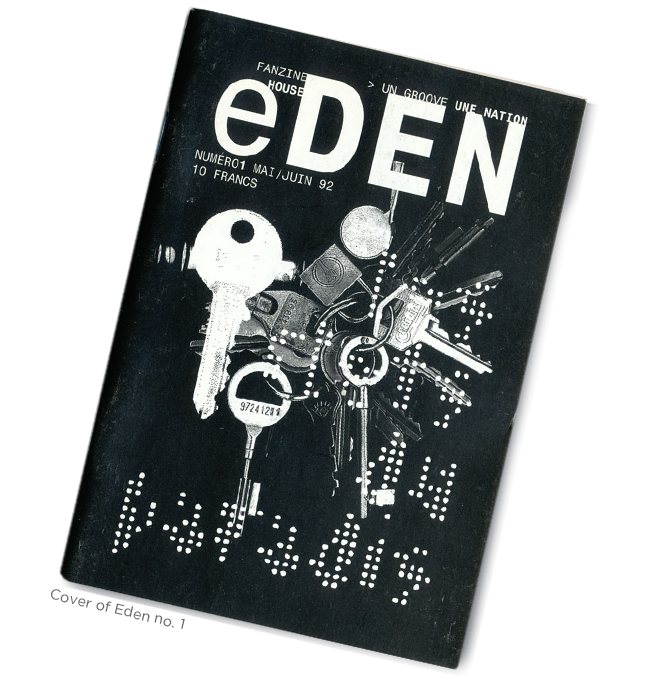

The first fanzine about house, techno, and raves was published in May. Instead of being sold at newsstands, the magazine was hawked at raves, clubs, and specialized record stores. The publication was very committed to the utopian values promoted by the movement during this foundational period. Entitled Eden, it considered raves and the new sounds being played there to be a sort of miniature heaven. The magazine was published by the musician Christophe Monier (The Micronauts), activist Christophe Vix-Gras, and graphic artist Michaël Amzalag. This last contributor brought an especially sleek design to this pocket-sized fanzine that proved to be a key factor in its success. All of its writers worked on a voluntary basis, including experienced journalists such as Vincent Borel, David Blot, and Didier Lestrade as well as artists who decided to try their hand at writing such as DJ Deep, Sven Løve, Alan Braxe, and D’Julz. It was also where Loïc Prigent, who would go on to become a famous fashion journalist, wrote his first articles. This dream team ran the fanzine for two years, publishing seven issues at irregular intervals. The articles discussed record releases and raves and included biting critiques of specific figures as well as enthusiastic editorials. The issue of drug use was examined openly but not idealized. A number of DJs also publish their playlists in the magazine. Mia Hansen-Løve’s 2014 film Eden examines the career of her disillusioned brother, the DJ Sven Løve, and is named after the fanzine, which remains a cult classic.

The rave craze started to catch on outside of Paris. In the spring, Marseille hosted the first Atomix party in the Friche Belle de Mai cultural center. Located downtown and easily accessible, it attracted thousands of dancers. A local scene started to develop ; notable DJs included Jack de Marseille and Olive. Other large raves were held in the region, including Euphoria and Dragon Ball.

When Boy closed down, the club’s owner, Philippe Fatien, bought out Le Central and renamed it Queen. Located at number 102 on the very chic Champs-Elysées Avenue, the large gay club could host over 2,000 revelers. House music featured prominently in the club’s line-up, which was overseen by house DJs Brainwasher and Charles Schillings as well as artistic director David Guetta. Later, Queen hosted the famous Respect parties.

Founded in 1991, the Fnac Music Dance Division released its first compilation, Respect for France, in an effort to introduce the world to French techno. In a generous move, it included the label’s own artists as well as those of Rave Age, Manu Casana’s record label. A promotional tour with Laurent Garnier, Shazz, and Ludovic Navarre was dispatched to clubs outside of Paris to help popularize the genre.

A collective of English ravers equipped with trucks, a sound system, and paramilitary style arrived in France to great fanfare. Spiral Tribe introduced the French to free parties and a wandering lifestyle. Spin-off groups were formed in their wake, including the Nomads, Psychiatrik, OQP, and Teknokrates. The first Teknival festival was held the following year near Beauvais.

The fourteenth edition of the Rencontres Trans Musicales de Rennes, a contemporary music festival organized by Jean-Louis Brossard and Hervé Bordier, welcomed this new generation of electronic music for the first time with a rave. A rather unsurprising move considering the festival’s emphasis on discovering new music. The ensuing Rave Ô Trans was primarily the result of a single meeting between Hervé Bordier and Manu Casana (Rave Age Records) during the New York Music Seminar 92 in New York. Casana brought Bordier to a rave in Brooklyn where Frankie Bones was playing. Bordier was quickly convinced that techno would be a good fit for the festival and tasked Casana with organizing the program for the closing night. While the press, festival technicians, and a portion of the audience were not very enthusiastic about the show leading up to the event, the artists asked to perform that night pulled out all the stops to win them over.

The line-up was exceptional and mostly included live performances. Among the performers were the English bands The Orb and 808 State as well as the American musical collective Underground Resistance, whose militant, hard-edged approach sparked a miniature riot in the audience. French music was also represented by Juan Trip, Pills, and DJs Pascal R and Jack de Marseille. The performance finally earned techno an official place in a recognized festival, and Brittany became one of the music style’s main strongholds. The “Trans” festival continued to include raves for many years to come, hosting a second Rave Ô Trans in 1993 followed by its Planète parties. Electronic music continues to be a favored music style in the festival to this day.