Nostromo flyer

Fantom, a group of young party organizers, held a rave called Nostromo in a hanger in the Parisian suburb of Issy-les-Moulineaux. The ambitious group rented the venue several weeks in advance to build an impressive set design and booked the American artists Blake Baxter and Juan Atkins. They also enlisted the graphic novel author Moebius to design the event’s video projections. A few months before the authorities would start their crackdown, five thousand people took part in what would prove to be the “authentic” rave era’s grand finale.

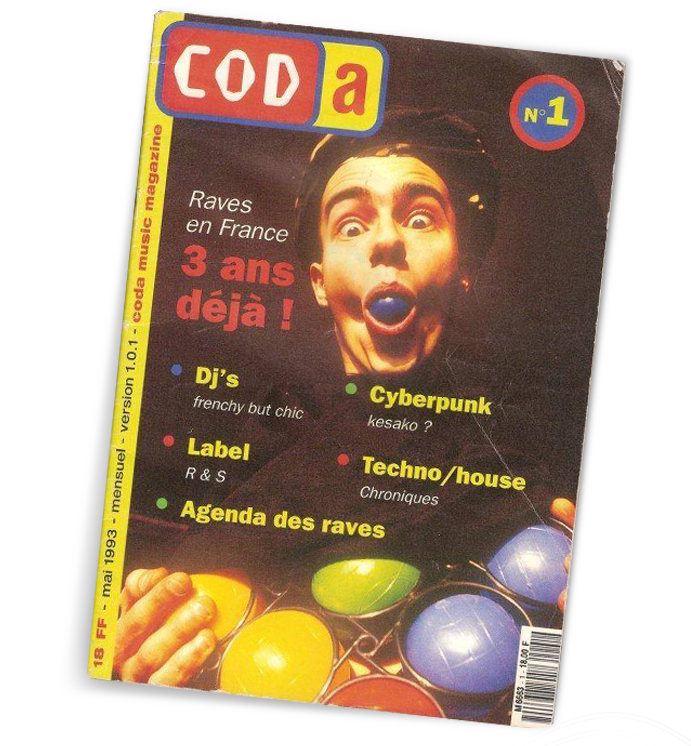

Though the techno and house scene was growing in France, it still didn’t have a “Bible,” i.e. an official magazine. There was Eden, but this low-budget fanzine wasn’t distributed through traditional newspaper circuits. Cue Eric Napora, a rave organizer with Cosmos Fact (Mozinor) and record dealer with the store TSF. Napora teamed up with Paulo Fernandes, a promoter with Happy Land, to start the magazine Coda. In musical parlance, a coda is a reprise, a repeated passage in the music. It was a fitting title for a magazine about techno, which is a repetitive musical style par excellence. The publication was widely distributed throughout France and was initially published every two months. It switched to a monthly schedule in April 1995. At a time when the rock music press continued to ignore, if not outright disparage, electronic music, Coda became the gold standard. The magazine decided to not feature artists on its covers in order to stand out and invent a new form of journalism in the music industry. Instead, its covers included photos of anonymous ravers or digital artwork. Young journalists earned their stripes in its columns, including Jean-Yves Leloup, Jean-Philippe Renoult, and Étienne Racine. Coda’s photos were also professional quality and often exclusive thanks to the contributions of photographers Pierre-Emmanuel Rastoin and Olivier Degorce. The magazine worked to present techno, house, and their derivatives as a genuine culture and not just a simple “sound” made for the dancefloor. Coda pursued this calling for several years until the arrival of its main competitor, Trax, in 1997. After adjusting its editorial line several times, changes that included finally featuring artists on the cover, the magazine published its last issue in 2006.

Coda’s first edition

Fnac’s new recruit, Guillaume Leroux, also known as Lunatic Asylum, released his maxi-single Techno Sucks Vol 2. It included the trance number “The Meltdown”, whose melody was inspired by the soundtrack from Dune by David Lynch. The song was performed by Sven Väth during the 1993 Love Parade and became the event’s unofficial anthem. It was the first French techno production to be successful abroad; nearly 30,000 copies were sold in just a few months.

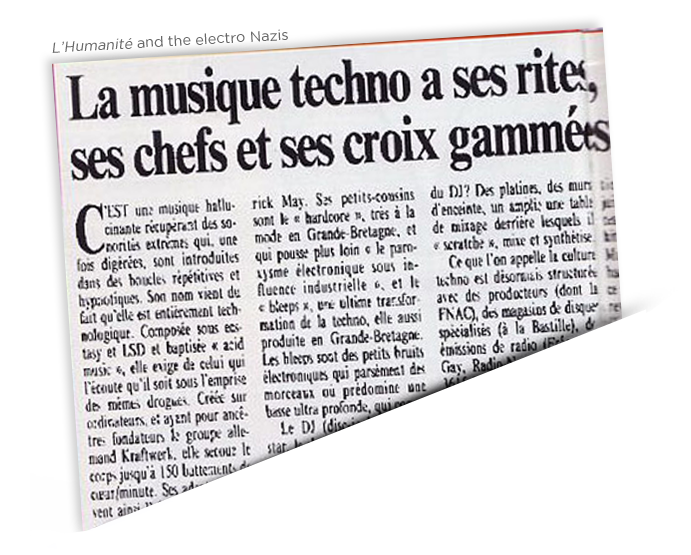

Low blows sometimes come from where you’d least expect them. The most virulent articles about techno and raves weren’t published in France’s conservative media outlets, like Figaro and Valeurs actuelles, but the newspaper L’Humanité. On June 15, 1993, not one, but three scathing articles appeared in the official organ of the Communist Party in the wake of a large rave, dubbed “Célébration,” held in the Grande Halle de la Villette to mark the twentieth anniversary of the newspaper Libération.

Whether it was simply a matter of revenge between two rival papers or something else, we’ll never know. The three articles, somberly entitled “Rave Phenomenon: A Mix of Loneliness and Drugs,” “Read on 3614 RAVE: Get Me Out Of This Hellhole,” and, the most salacious of the three, “Techno Music’s Rituals, Leaders, and Swastikas,” proved to be a flashpoint. The authors alternated between spreading pure disinformation and trotting out every cliché imaginable. According to them, techno “insiders” were really part of a cult; raves were just an excuse for drug consumption; the music was deafening; and young ravers were destitute, desocialized individuals not much different from “zombies.” The parts that addressed techno music and artists were more humorous: “Written with ecstasy and LSD, this acid music requires anyone listening to it to be under the influence of these same drugs.” On a more serious note, the article mentioned groups from the post-punk industrial scene like Death In June and Vomito Negro, which did in fact incorporate references to Fascism, most often in a figurative sense. However, the journalists forgot to point out these groups had absolutely nothing to do with the rave scene in the 1990s. The fallout was disastrous. A dispatch from the eminent Agence France-Presse echoed the articles’ alarmist tone, and regional media starting to condemn rave culture as well. It was the start of the demonization of techno and its large-scale repression by the authorities.

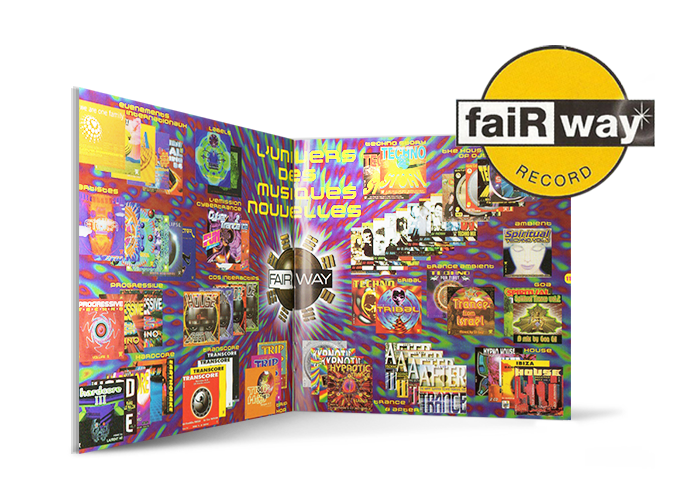

A label specifically dedicated to DJ mixes and compilations was founded in June 1993. Fairway, directed by Daniel Goldsmith and Olivier Planeix, had a substantial budget at its disposal, which it used to promote and distribute its music. The label’s compilations were educational in nature and often dedicated to specific musical genres. Fairway released a series of records, including Transcore, Hardcore, Progressive, and Hypnotic Trance—most often with French artists running the turntables.

After L’Humanité published its ruthless anti-techno articles, things took a turn for the worse for “House Nation,” as the techno, house, and rave movement called itself at the time. Just like Mayday in Germany and Universe in England, the Oz rave, scheduled for July 10, 1993, was supposed to be the movement’s biggest rave ever. The event, which was organized by Coda and Laurent Garnier, was supposed to bring no fewer than 18,000 people from all across Europe to the Amiens Expo Center. A record 1.2 million francs were spent on the rave. Two hundred thousand full-page color flyers were distributed throughout France and neighboring countries. Over forty artists, including Carl Cox and Sven Väth, were supposed to perform on three separate stages. Even as talks with City Hall were progressing nicely, an article published in Courrier Picard jeopardized the entire effort. It described the hordes of hooligans who were getting ready to invade Amiens, which would be turned into a focal point for the drug trade during the event.

Flyer from the Oz party

The day before the opening act, after all the equipment had already been installed, the police issued a decree cancelling the rave, citing the risks of a public disturbance and their inability to provide security at the event due to the arrival of the Tour de France in the region. All the money spent on organizing the event was lost, and two sponsoring stores, TSF and USA Import, were forced to shut down. Radio FG aired debates on the topic, and a spontaneous march was held at Paris’ Trocadéro Square in solidarity. Spiral Tribe, one of the groups invited to perform at Oz, set its sound system up on Ile aux Cygnes in Paris. Two weeks later, they organized the first teknival in a field near Beauvais.

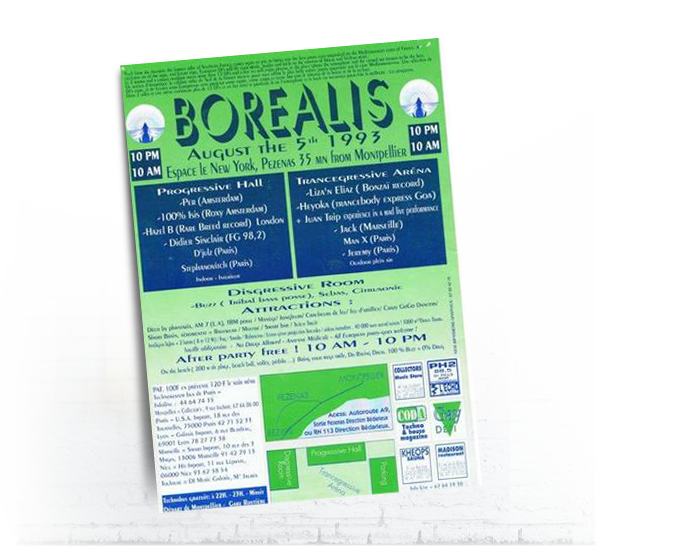

In Montpellier, a group of friends by the name of “La Tribu des Pingouins” started a rave called Boréalis. Before it moved to Nîmes’ Roman amphitheater, the party’s first edition was held at the club Pézenas and the adjacent parking lot. Over 2,000 people danced to sets by Liza N’Eliaz, Juantrip’, Stephanovitch, Heyoka, 100 % Isis, and Jack de Marseille. It was the start of a great adventure.

Flyer for the first Boréalis

Yellow Productions was created in the fall of 1993 by Alain Hô (DJ Yellow) and Christophe Le Friant, who hadn’t yet adopted the name of Bob Sinclar. The label first sought to break out of the mold of traditional house music, featuring acid jazz and trip-hop with Latin and Brazilian influences instead. Yellow Productions became one of the leading producers of “chic” French-style music. It later became much more commercial in nature when it started releasing Bob Sinclar’s music.