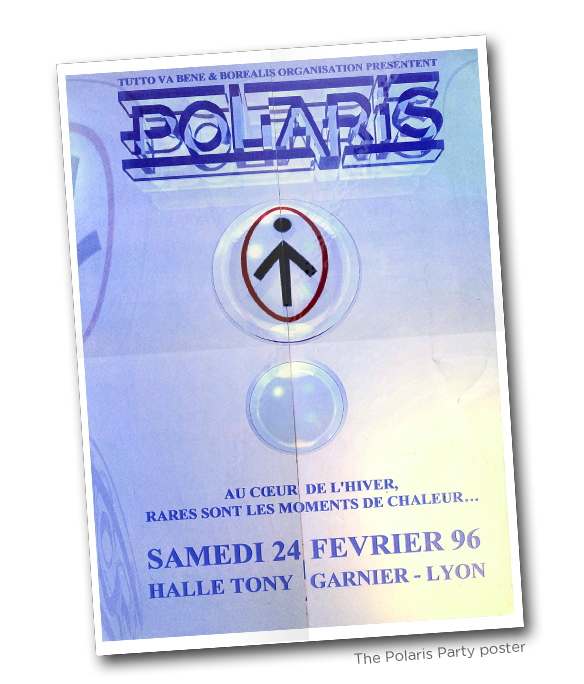

Ever since the French Ministry of the Interior issued the memorandum “Raves: High-Risk Events,” organizers who were still trying to host legal parties were faced with a host of cancellations. Police decrees and nitpicky safety commissions pulled events at the last minute, leaving many organizers discouraged. Some, including Max le Sale Gosse, were even jailed simply for hosting a party. A portion of France’s ravers turned instead to free parties, which operated completely outside the bounds of the law. In Nîmes, due to the misdeeds of unticketed fans the previous year, city authorities refused to host the Boréalis rave in the Roman amphitheater. Its organizers, La Tribu des Pingouins, planned instead on holding a winter event. Polaris was scheduled to take place on February 24 in the Halle Tony Garnier, Lyon’s largest concert venue. In principal, the event should have gone off without a hitch. The organizers were clearly thorough and conscientious, the auditorium was up to standard, and the set included first-rate artists like The Prodigy, Carl Cox, and DJ Hell.

However, Lyon Mayor Raymond Barre, under pressure from the region’s night club union, which worried about losing its clientele, ordered the party to end at 1:00 a.m. At the time, people weren’t yet used to attending daytime events. Techno was for night owls. With great reluctance, the Pingouins were forced to call off the rave. It proved to be the last straw. Following this de facto cancellation, a professional association called Technopol was created. Its goal was to defend and obtain recognition for electronic music culture and its affiliated stakeholders. The group was also in charge of organizing the Techno Parade starting in 1998.

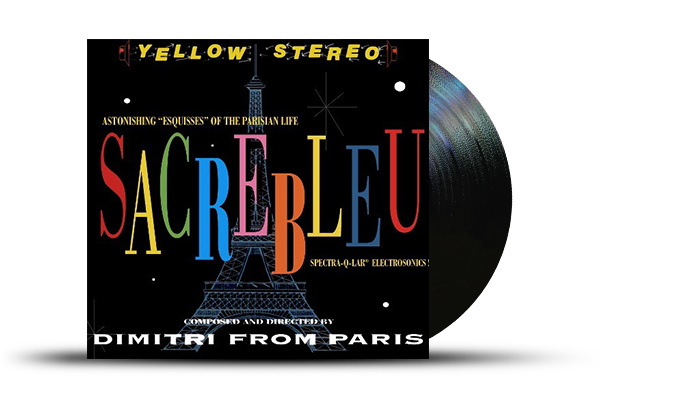

Dimitri from Paris was a long-time DJ who started playing disco, house, and garage music in the late 1980s on his radio show “NRJ Club.” In June, he released his first album, Sacrebleu, under Yellow Productions, Bob Sinclar’s record label. The record veered towards downtempo and easy listening with samples that pulled heavily from jazz. Sacrebleu was unabashedly kitsch and played up French stereotypes, especially in the track “Sacré Français.” It was also a major international success. Following the release, English journalists started using the term “French touch.”

There was now enough French electronic music to start packaging it into compilations. A Virgin sublabel released Source Lab 2, and Level 2/F Communications came out with Art of France one month later. The first sought to bottle the new Paris-based “French touch” scene, while the second offered a historic retrospective ranging from the house music of DJ Deep to the hardcore sound of Manu le Malin.

While most raves featured hardcore and trance, some organizers continued to host parties outside of the club scene that were geared towards a warmer sound.

Le château de Vaulx-le-Pénil

Such was the case with Fred Agostini, whose Xanadu events featured all future “French touch” artists, including Daft Punk, Cassius, Gilb’r, and Ivan Smagghe. However, the party held in July at Vaux-le-Pénil Castle ended with an aggressive police raid. Fred Agostini was brought into custody the next day. A few months later, he started organizing parties again, but this time in clubs. At Queen, he launched the Respect parties soon after.

Now that the French electronic scene was finally being taken seriously, a number of labels were created in the mid-1990s. Many of them were independent and focused on producing vinyl, which was the favored medium of the vast majority of DJs. The most important names included the historical F Communications as well as Solid, Omnisonus, Logistic, Pro-Zak Trax, Pschent, Serial, and many others. Today, most of them have disappeared as a result of the record industry crisis, but a few have managed to weather the storm, including Bertrand Burgalat’s Tricatel. While it is not solely an electronic label, it is associated with the genre for its easy listening releases. Yellow Productions is still active, but nowadays hardly releases anything other than Bob Sinclar productions. Versatile continues to be a mainstay in the French electronic scene. The label was founded by the DJ Gilb’r, who left Radio Nova to strike out on his own in the summer of 1996. Inspired by New York record labels like Strictly Rhythm for the house institution’s dancefloor vibe and English labels like Warp and Ninja Tune for their adventurous approach, Versatile’s first two releases “Disco Cubizn” by I:Cube and “Venus (Sunshine People)” by Cheek, were highly successful. However, Gilb’r didn’t want to be limited to the filtered house sound that was in fashion at the time. He ventured off the beaten path for the label’s second release by signing Zend Avesta, one of Arnaud Rebotini’s pseudonyms. Ever since, Versatile has promoted open-mindedness and musical curiosity—watchwords that have doubtless contributed to its longevity.

The label discovered important artists in the 2000s and 2010s, including Joakim, Zombie Zombie/Etienne Jaumet, and the duo Acid Arab. The pioneering labels from the 1990s cleared a path for those that came after like Ed Banger and Institubes, who held on to the same independent attitude and promoted CDs and vinyl along with digital formats.

In addition to playing a pivotal role in the history of French house, Pansoul was also a legacy album. It provided the best possible conclusion to the work of Motorbass, a duo composed of Philippe Zdar and Étienne de Crécy. Their silky-smooth house, which drew from African-American electronic music, was subtly produced and featured samples as numerous as they were unrecognizable. The first pressing sold out quickly and became a cult classic among record diggers. Virgin re-issued the album in 2003.

At the opposite end of the spectrum from French touch, which was taking the world by storm by this time, Lille producer Emmanuel Top released his most ambitious album, Asteroid, under the English label Novamute. Though his trance project, BBE, was hugely successful and profitable, the album marked a return to his acid techno roots. Asteroid featured a very minimalistic approach that was doubtless inspired by the work of Richie Hawtin. Though house music had captured the media’s full attention, France’s music scene hadn’t heard the last from techno.

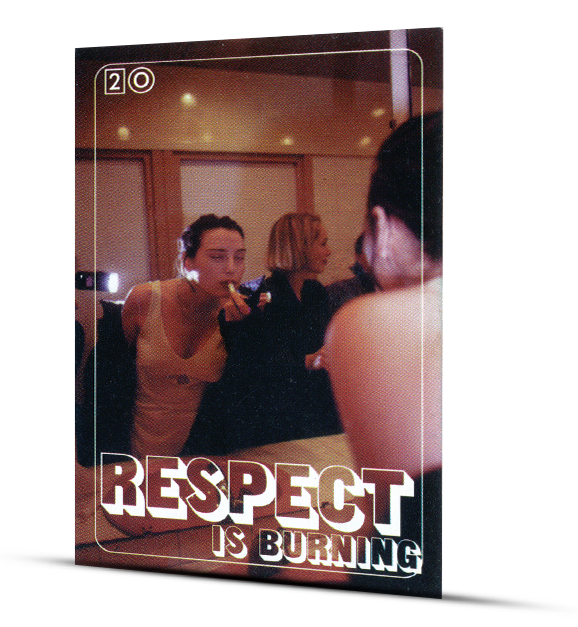

Queen, the Champs-Élysées’s famous gay nightclub, hosted its first Respect party in the fall of 1996. With Daft Punk headlining, the event was an immediate success. Two journalists, David Blot from Radio Nova and Jérôme Viger-Kohler from Radio FG, as well as Xanadu’s host, Fred Agostini, were behind the new party.

They had two goals. First, the organizers wanted to create a genuine club culture in Paris fashioned after that of New York to move away from the traditional nightclub model, which didn’t place much stock in quality music. They invited American house legends like David Mancuso from Loft and Joe Claussell. Secondly, and most importantly, they wanted to create a decent space where France’s ebullient electronic scene, which was causing such a buzz abroad, could finally take shape and grow. Indeed, Cassius, Etienne de Crécy, Dimitri From Paris, and other electronic artists were rarely asked to perform locally. While the Rex Club did book some DJs, it ascribed to a rather purist view of techno founded in the Detroit tradition and rave culture. Respect was a free party held every Wednesday night with a very tolerant door policy and a friendly atmosphere. Celebrities and penniless students danced side by side to music that was exceedingly modern. Photographer Agnès Dahan designed the event’s flyers, which looked like collectable cards and contributed to Respect’s cool, glamorous aesthetic. The deal was sealed a few months later when the party crossed the Pond to land at New York’s Twilo, where American clubbers fell in love with France’s DJs. There was even a Respect party in Los Angeles at the famous Playboy mansion of Hugh Hefner, the erotic magazine’s founder. Before Respect, French touch music could only be found in record bins. The party brought it into clubs the world over, forever transforming Paris’ party scene.

Now free from the duo Motorbass, Etienne de Crécy was ready to spread his wings as a solo artist. Super Discount was a concept album about consumerism that included collaborations with other artists such as Air, Alex Gopher, and… Philippe Zdar. The album had a “filtered” house sound that drew from multiple influences. With its music videos and interlocking sleeves, Super Discount also emphasized visual media.

The Internet became available to the general public in 1996 in France. Of course, connection speeds were extremely slow and browsing time was limited—AOL offered twenty hours per month, for example. Nevertheless, the “network of networks” opened the door to unprecedented opportunities. The entire world became accessible with a few clicks of a mouse. It profoundly changed every aspect of life, especially music.