The year 1997 was a real turning point in the history of the French electronic music scene due in large part to the release of Daft Punk’s album, Homework, in early January.

Since their 1995 maxi single “Da Funk/Rollin’ & Scratchin’,” a growing number of listeners had started to clamor for a full Daft Punk album. All major record companies competed with each other to sign the Parisian duo, and, in the end, it was Virgin who won out due to the efforts of its director, Emmanuel de Buretel. The move broke a taboo in the techno/house scene, which up to that point had jealously guarded its independence. Homework was widely distributed internationally and lavishly promoted. For the first time ever, electronic music, which had been relegated to the underground scene and dogged by a negative reputation, was stocked on supermarket shelves and available to a wider public. Aware that such a level of exposure was going to change their lives forever, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homen Christo decided they didn’t want to become rock stars; from that point on, the musicians always performed with masks. Musically, the record was still heavily influenced by traditional techno and house, especially the styles coming out of Chicago.

In fact, “Teachers” was an overt tribute to a number of producers from both scenes. The album also kicked off a frenzy for what was called the “French touch,” and multiple artists strove to reproduce Daft Punk’s sound with compressor-enhanced disco and funk samples. Homework was incredibly successful, selling over two million copies worldwide. However, the rock music press continued to turn its nose up at a genre it still struggled to understand; French magazine Les Inrockuptibles lamented an “unfortunately exhausting album.” Electronic music still had a ways to go.

Laurent Garnier’s album, 30, was released in April and featured one of his biggest classics, “Crispy Bacon”. Garnier was invited on television shows, including “Nulle Part Ailleurs” on French station Canal +. Several videos from the album, such as those for “Crispy Bacon” and “Flashback,” were produced by Quentin Dupieux, who had not yet adopted the pseudonym Mr. Oizo. The following year, the album became the first of its kind to win a Victoire de la Musique award in the “Dance” category.

After hosting a few house music events in previous years, the Printemps de Bourges music fest collaborated with a promoter from Annecy to organize a giant rave called Hexagona 97.

Attended by over 5,000 people, the event confirmed techno’s place in the traditional music festival line-up. The party was even broadcast live on NRJ radio and featured a very international set that included Carl Cox, Jeff Mills, Richie Hawtin, Joey Beltram and Luke Slater.

Poster for the Hexagonale 97 rave

The legal rave D-Mention, put on by the Rex Club’s current director, Fabrice Gadeau, was held in Rungis despite considerable opposition. The police had ordered the safety commission to create trouble for the party’s organizers, who were forced to provide nearly 3,000 chairs for a dance party and drastically reduce the number of guests. Many were still somewhat wary of techno.

Libération article about the D-Mention party

Working at the opposite end of the spectrum from the house and French Touch sound that was in vogue at the time, DJ Manu le Malin decided to release the first volume of his mix series, Biomechanik, in the spring of 1997. Inspired by Swiss artist H.R. Giger, whose work included the monster from the movie Alien, the compilation popularized dark, hip-hop-infused hardcore. After a few years of regularly playing raves and free parties, Manu’s style took on elements from both the German scene, with its austere sound, and the New York scene, which tended towards a more “gangsta” interpretation of the genre.

The CD, which was released under Level 2, a subdivision of Laurent Garnier’s F Communications record label, was more widely distributed than other hardcore albums. Up to that point, hardcore was mostly released on vinyl and only stocked by specialized record stores, with the exception of Dutch compilations, which were much more sensationalist. Biomechanik let listeners who weren’t vinyl enthusiasts or ravers discover another side of hardcore they weren’t necessarily familiar with before. Manu le Malin’s technical skill at the turntable made the music’s severe sound more approachable. Paradoxically, however, Biomechanik was released during a pivotal time in which the French hardcore rave scene, led by DJs like Liza N’Eliaz and Laurent Hô, was disappearing in favor of free parties, which tended towards less complex music.

The publisher Freeway, which has since closed down, starting issuing a new magazine, Trax, in July 1997. It was aimed at a wider audience than the historical Coda magazine and hoped to capitalize on the popularity of French Touch. Trax featured well-established artists and came with a ten-track CD every month. Alexandre Jaillon, now Deputy Director at We Love Art, an organization that puts on a number of events and festivals including the We Love Green music fest, was hired as its first editor-in-chief.

In Brittany, on the heels of Astropolis’ first two editions, one in a field and the other in an exhibition center, the 1997 festival took place in Concarneau’s Kériolet Castle for the first time. The owner was delighted to host the thousands of ravers. Liza N’Eliaz and Jeff Mills performed a back-to-back anthology set.

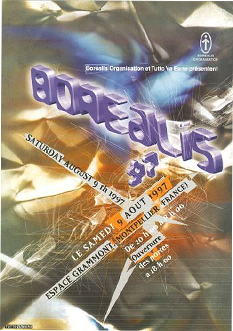

Another major summer event, Boréalis, had outgrown Nîmes’ Roman amphitheater and so moved to the immense Espace Grammont in Montpellier. With nearly 25,000 attendees, it was the largest techno event to ever be held in France. The festival included performances by Daft Punk, Chemical Brothers, Laurent Garnier, and even the experimental electronica band Autechre.

Electronic music became the music of an entire generation with the success of Daft Punk and French Touch. Though it had long been relegated to cable (120 BPM on MCM), the genre now had a monthly show on the French national channel M6 called “Techno Max.” It was named after the host, Max, who was somewhat of a narcissist and also a host on Fun Radio.

Even public channels and educational programs started looking at techno from a cultural, sociological, and rather positive angle. “Envoyé Spécial” was one such example. At the end of the year, it broadcast a report entitled “La France qui Rave” [Raving France]. Directed by Nicolas Winckler, a young journalist with an off-beat approach, it didn’t ignore the drug issue, but didn’t linger on it either. Instead, the special focused on interviews with artists, label owners, radio hosts, journalists, organizers, and young partygoers. The insightful program also picked up on an underlying sense of class conflict behind the competing currents starting to form within the movement. It featured proponents of illegal free parties that cost nothing to attend, students who favored large organized raves, and a more well-heeled club scene in which French Touch was quickly gaining traction. “La France qui Rave” also educated viewers about DJs’ artistic skills, the central role they played during parties, and how many were shifting from mixing to composing and producing music. The show also asked the various people involved in electronic music to explain the values and ideologies behind the new sound, which some had accused of lacking any sense of purpose or meaning. Finally, the program addressed the exploitation of techno by politicians, the business world, and major companies. The media attention came at a pivotal time for the French electronic music scene, which had long been marginalized and demonized.