The memorandum issued by the Ministry of the Interior

While England was enacting its Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, authorities in France preferred using backdoor policies in their attempts to curtail a cultural movement that remained largely misunderstood. The repression of the electronic music scene had started two years previously with the sensational cancellation of Oz rave in July 1993. However, the ministerial memorandum “Raves: High Risk Events” only made the situation worse. Distributed to police commissioners, police departments, and the French national police force, it presented a distorted view of the techno movement and gave instructions on how to best prevent parties from occurring. The document’s many imprecisions and misstatements made for entertaining reading, but in reality were chilling given that the text was doubtless written by France’s intelligence services. One of the memorandum’s main takeaways was that techno music went hand-in-hand with drug consumption. The DJs and artists who performed during raves were potential dealers that needed to be closely monitored. This text had a devastating effect on organizers who were trying to host parties via the legal route. Events were cancelled left and right. Indirectly, the memorandum accelerated the spread of underground free parties, which took place outside of any kind of legal framework. In Paris, the directors of Radio Nova, Radio FG, and Libération were even summoned to police headquarters. They were accused of “complicity to traffic drugs” because they advertised electronic music events in the newspaper or on the radio. It wasn’t until 1998, when another memorandum was issued with a much more open stance towards techno, that tensions finally eased.

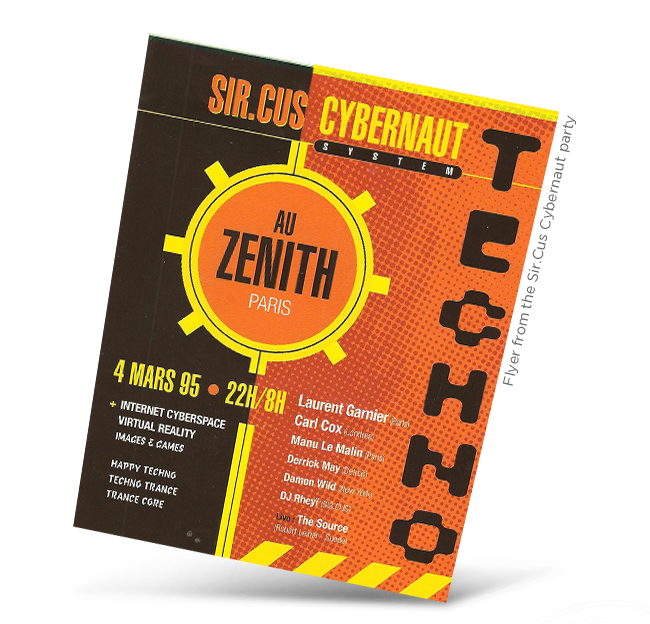

Even though the backlash against techno had reached its peaked by this time, Paris’ Zénith concert hall hosted its first techno show without incident. Organized by the “Allumés de Nantes,” the event, called “Sir.Cus Cybernaut System,” was presented not as a rave, but rather a celebration of cyberculture and multimedia performance. Carl Cox, Derrick May, Laurent Garnier, and Manu le Malin all took turns in the booth.

A young, virtually unknown French duo, Daft Punk, released their second maxi single under the Scottish label Soma Quality Recordings. The B-side featured a techno hymn entitled “Rollin’ & Scratchin’” whose erratic, aggressive rock’n’roll sound was tailored for the rave scene. On the record’s A-side, “Da Funk” featured a slower rhythm, gleefully offering a reinvention of disco sound with an obsessive melody and a sweeping acid bassline. The record was an instant classic and proved to be the start of a great adventure.

St Germain released his album Boulevard with F Communications, the label owned by Laurent Garnier and Eric Morand. Ludovic Navarre (his real name) was one of France’s first house and techno producers. In 1991, he released the track “Subhouse” under Belgium record label Atom. The song was a huge hit in Belgian clubs. Navarre then signed with Fnac Music, the predecessor of F Com, where he participated in multiple projects and collaborations with Shazz, DJ Deep, and Laurent Garnier himself, including helping to produce the classic “Acid Eiffel.” Under the pseudonym Deepside, he created melancholic music influenced by the Detroit scene that even gained him accolades from his American peers. However, Ludovic Navarre quickly grew tired of the cookie-cutter nature of the techno scene and businesslike productions designed for the dance floor. His St Germain project, which he started in 1993, featured a more downtempo sound that drew heavily from jazz and blues. Three years later, he started playing with musicians who improvised freely over his electric base. The result was his album Boulevard, a resounding success that sold over 200,000 copies. The record featured classy, jazzy-sounding house music that made it a bona fide precursor of French Touch before the trend was eventually denatured by a flurry of filtered samples.

Following this success, St Germain took time to refine his productions. In 2000, St Germain’s second masterpiece, Tourist, paid tribute to the blues and was released under the legendary American jazz label Blue Note. The general public then took notice, and record sales were staggering—four million copies were distributed throughout the world. Exhausted from a long tour and not wanting to make the same kind of music twice, Ludovic Navarre seemed to have run out of inspiration. He disappeared for nearly fifteen years, only to come back suddenly in 2015 with an eponymous album, this time inspired by West African music.

Among the many labels that popped up in the mid-1990s, some of them proudly proclaimed their French origins—proof that being a French artist on the international scene was no longer a stumbling block. POF, meaning Product of France, was founded by Fred Giteau and Olivier le Castor and distributed under Labels/Virgin. The record label primarily carried techno and trance music.

Paris’ Rex Club starting playing electronic music exclusively in the fall of 1995. Originally a fashionable dance hall known as Le Rêve and later a concert venue, Rex Club hosted France’s first acid house parties as early as 1988 thanks to support from its director, Christian Paulet. However, the event that really pushed the club to switch to electronic music completely was Wake Up. Organized by Laurent Garnier and Eric Morand starting in 1992, these parties featured legendary artists from Detroit and Chicago. Other weekly events that helped cement Rex Club’s reputation at the start of the decade included David Guetta’s Unity, Pierre Hermann’s Temple, and Space by Cypriano Munoz. Over the years, the club’s audience changed, and the Rex Club transformed itself in response. The stage design was completely overhauled, and the building’s décor was given a minimalistic makeover featuring orange and blue walls. A new sound system was installed, and, in a symbolic move, the DJ’s booth was moved to the old stage, bringing it even closer to the audience. The club played all types of electronic music and invited a new organizer to host a party every night. Some notable examples included DJ Deep’s Legends, Gilb’r’s Rollin, and more recently Fabrice Gadeau’s Automatik, Djul’z’s Bass Culture, and Elisa do Brasil’s Massive. Every major artist in electronic music has played the Rex at least once. Other clubs outside of Paris, including the An-Fer in Dijon, Hypnotik in Lyon, and 4Sans in Bordeaux have also tried to follow Rex Club’s example. While the Parisian scene is more competitive than ever today, the Rex remains the oldest electronic music club in the world.

Psychedelic trance, which is still called Goa trance in reference to the Indian hippie parties where it originated, became the most popular electronic style in 1995. It was actually produced by English and Israeli artists for the most part, but French groups left their mark as well. The Bordeaux trio Total Eclipse, which was clearly the most talented group active in the sub-genre, released its first album Delta Aquarids at the end of 1995.